Alok Nandi: The Future of Design is Now

Creative director, speaker, consultant, teacher and author – this multi-faceted designer and theorist gives TLmag his vision on the past and future of design and the profession of the designer in relation to the COVID-19 crisis.

TLmag: Tell us about your career path.

Alok Nandi (AN): I am a civil engineer by training. During my studies, I became interested in cinematography, which led me to learn screenwriting. I was then invited to work on the design of a book and an exhibition for the Cannes Film Festival. At the beginning of the 1990s, I embarked on a deep reflection of the behavioural rationales, what Anglo Saxons call ‘patterns’, that influence how one navigates a book, an exhibition, but also a website. I have explored this area at great length, mainly with regard to comic books. The many projects I have been involved in, even now, have enabled me to immerse myself in concepts of contemporary design, at the crossroads between technology and the understanding of human behaviour.

TLmag: You emphasise the misunderstanding that surrounds the very definition of the word design.

AN: The definition is limited to the concept of object design. It’s terribly reductive, but also counterproductive – since this misunderstanding of what the term encompasses prevents us from exploring it as much as we should. To clarify my point, I like to speak of ‘Design with a capital D’, that is to say, expert design – which is the one I just mentioned and is, in French, the only one – as opposed to the other, “design with a little d”, diffused design. The first aims to resolve what I call contradictory constraints. At the global level, it only accounts for 10%, even 15%, of the domain covered by design in the general sense. Isn’t it high time to broaden our horizons and our activities? In the past 30 years, the concepts of design have greatly expanded. They no longer have anything to do with industrial design, born 150 years ago. In French-speaking countries, this new reality is very rarely taken into account in the thinking of political decision-makers. This is paradoxical since today there is a lot of talk about creativity. People dream of being inventive without realising that this design, because it meets society’s expectations, in terms of well-being, for example, is an opportunity to put their inventiveness to work on society’s new challenges and expectations. And it isn’t artificial intelligence that will be the contributing factor, but the fertility of the human spirit. To achieve this, it is necessary to educate the general public in order, on the one hand, to encourage new vocations among young people and, on the other, to inform parents through the media, in particular, so that they, in turn, can broaden the knowledge base of their children.

TLmag: This approach also involves an overhaul of the systems for design education.

AN: So far, I’ve talked a lot about the concept of design; a design that goes beyond the idea of creating a new chair, but that also applies to fashion. It is high time to leave behind the traditional pattern of the star designer communicated by the press and large luxury groups, and to centre teaching around the concept of 21st-century craftsmanship, which combines the dynamism of the hand and cognitive skills. Today, a baker must master both the basic movements of his trade and also broaden his thinking by manipulating certain tools and knowledge (in the leavening field, among others), allowing him to create new breads that correspond with our expectations in terms of environment, health and well-being. Likewise, in the courses I teach at the Paul Bocuse Institute, I explore the very essence of the profession of cooking. I try to show the students, always using this systemic approach to design, that a chef is a designer and that his area of reflection goes far beyond the idea of a dish that is beautiful and tasty. For a chef, a good philosophical stance includes a reflection on products, their origin, etc. For a fashion designer, it includes, for example, the questioning of seasonality. Now is the time to question all of these patterns.

TLmag: You say that the COVID-19 crisis has helped to open the public’s eyes to certain issues. Is it a question of ‘now or never’ to review certain systems and infrastructures?

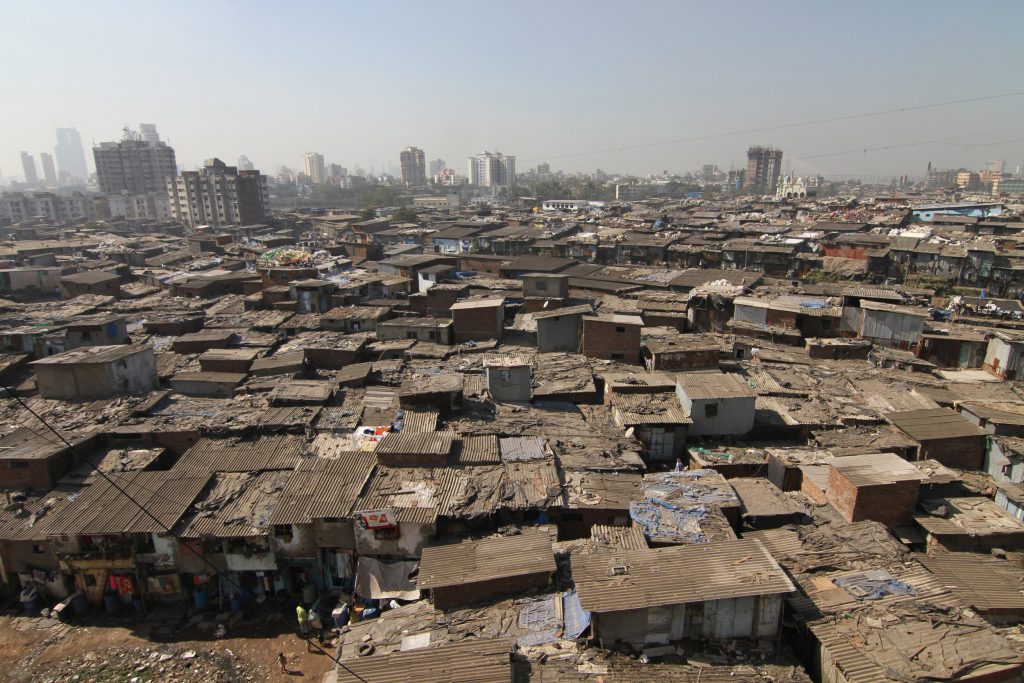

AN: Yes, especially as most date from the 19th century. Take mobility. Only cities that have or will question certain parameters of urban design will be able to move in the right direction. This is what the city of Ghent has done. As the city was aware that the streets in the centre were no longer suitable for today’s traffic, it chose to make them inaccessible to cars. Consequently, Ghent has become a city with a good quality of life and, economically, is doing very well. The advantage of urban design is that it is based on very long timeframes. In other areas, you have to act faster. This complicates the work of designers and decision-makers. In my opinion, the designer’s stance must rest on three axes: observation, humility and experiencing a trial and error phase (which is an integral part of the change process).

TLmag: At this time of great societal upheaval, design is now – more than ever – a driver of innovation. What do you think?

AN: To answer, I would like to come back to the concept of the profession of designer as I comprehend it, and to the plasticity inherent in this profession. When creating new systems and platforms, the designer must be able to speak to technicians, managers or even lawyers. The crisis we are currently experiencing has accelerated certain societal trends, particularly in the field of work. Take the example of the home office. With the imposition of confinements, companies, but also schools, have been forced to review their information and knowledge sharing systems. We see that 60-70% of these exchanges no longer require the sharing of a physical space by the various interlocutors. Now is the time to reinvent our practices and our work protocols. Addressing this issue touches on the concept of well-being which, as I mentioned, is fully in line with the fundamentals of design. Participatory design, a driver of change, must rely on both the creation of new scenarios, but also on the proactivity of sponsors, such as business leaders, who will take the risk to try these new operating modes before they can be systemised.

As a designer, author and creative entrepreneur, Alok Nandi works on hybrid systems. Building on experiences as creative director and design strategist, his blog, @nandi.mobi, looks at narrative and design, in their multiple dimensions and manifestations: interaction design, film, media, digital art, exhibition design, radio, publishing, graphic novels on web, festivals, PechaKucha live storytelling.

Attached imagery is courtesy of documentary filmmaker Gary Hustwit, featuring stills from his films Helvetica, Objectified and Urbanised.